The next Bitcoin halving event is set to happen on block 840,000. With an ETA of 232 days away, the next halving event will reduce the rate of new Bitcoin creation, reinforce Bitcoin’s scarcity, and have its way with miner economics, market sentiment, and long-term investment strategies within the crypto ecosystem. How to analyse and track the blockchain’s progress and why anyone would below.

Source: The New Yorker

Halving Explained

The Bitcoin protocol reduces the reward given to miners by 50% every 210,000 blocks, hence “halving”. It takes approximately four years to mine these blocks. Mining Bitcoin is the process of using specialised computer hardware which solves complex mathematical puzzles to validate and record transactions on the Bitcoin blockchain. In return, miners earn newly created Bitcoins and transaction fees as rewards.

Starting with the 50 BTC reward for early miners in 2009 and the subsequent halving events that reduced the reward to 25 BTC in 2012, 12.5 BTC in 2016, and 6.25 BTC currently. The next halving is due April 26, 2024, which will further reduce the block reward to 3.125 BTC. What is the purpose of Bitcoin halving?

The next Bitcoin halving event, like previous halvings, will achieve several significant outcomes:

- Supply Reduction: The primary purpose of a Bitcoin halving is to reduce the rate at which new Bitcoins are created and added to the circulating supply. This event cuts the block reward in half, meaning miners receive fewer Bitcoins for each block they successfully mine. This reduction in supply growth is crucial in managing inflation and scarcity.

- Scarcity: Bitcoin is often compared to gold due to its limited supply. With each halving, the rate of new Bitcoin creation slows down, making it increasingly difficult to obtain new coins. This scarcity drives up demand and increases the value of existing Bitcoins.

- Mining Economics: The halving event can impact the economics of Bitcoin mining. Miners who rely on block rewards for their revenue will face reduced income after a halving, potentially leading to some miners exiting the network if they find it unprofitable. This, in turn, can affect the network’s hash rate.

- Market Sentiment: Halving events capture significant attention from the cryptocurrency community and media. Anticipation of a halving creates a sense of scarcity and excitement among investors and traders, driving up market prices in the months leading up to the event.

- Long-Term Investment: Halvings reinforce Bitcoin as a deflationary asset with a fixed supply. This narrative attracts long-term investors who see Bitcoin as a secure store of value and hedge against inflation.

- Miner Adaptation: Miners must adapt to the reduced block rewards by improving efficiency, optimising operations, or exploring alternative revenue streams such as transaction fees. This process can lead to innovations in mining technology and practices.

- Network Security: While a halving may temporarily reduce the hash rate as less efficient miners leave the network, the overall security of the Bitcoin network is expected to remain strong due to the network’s difficulty adjustment algorithm, which regulates block production times.

- Historical Precedent: Halvings have historically been associated with significant price increases in Bitcoin, although past performance is not indicative of future results. This historical precedent can influence investor sentiment and decision-making.

While the next Bitcoin halving is expected to further reduce the rate of new Bitcoin creation, reinforce Bitcoin’s scarcity, and attract investors, certain miners view halving as a serious disadvantage. So, why do miners continue to dedicate computational power and resources to secure the Bitcoin network?

Why Miners Mine

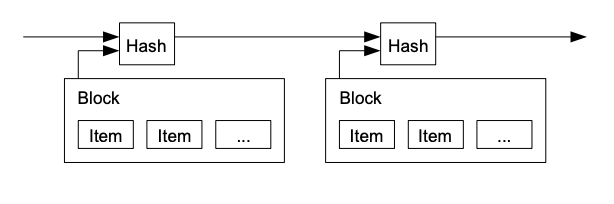

Bitcoin mining is a competitive process: miners continually attempt to find valid hashes faster than their peers. A hash is the result of applying a hash function to input data, meaning that hashrate is a measure of the computational power used to perform hashing operations. Hashrate is a critical factor in blockchain mining, as it determines a miner’s probability of successfully mining a new block and earning rewards in cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin.The difficulty of finding a valid hash adjusts approximately every two weeks to ensure that, on average, a new block is added to the blockchain every ten minutes. This process of securing the network through computational work and cryptographic puzzles is known as Proof of Work (PoW).

Bitcoin miners earn rewards in the form of newly created Bitcoins and transaction fees for validating and adding new blocks to the Bitcoin blockchain. Here’s how it works:

- Block Reward: Miners receive a predetermined number of newly created Bitcoins as a block reward for successfully adding a new block of transactions to the blockchain. Initially, this reward was 50 BTC per block, but has since been reduced by 50% approximately every four years through “halving”.

- Transaction Fees: In addition to the block reward, miners also earn transaction fees paid by users who send Bitcoin transactions. These fees are voluntary and are attached to transactions by users to incentivise miners to prioritise their transactions. Miners collect these fees for including transactions in the blocks they mine.

- Total Reward: The total reward a miner receives for adding a block consists of the block reward (currently 6.25 BTC) plus the sum of transaction fees from all the transactions included in the block. This total reward varies from block to block.

Mining rewards provide an incentive for miners to dedicate computational power and resources to secure the Bitcoin network, validate transactions, and maintain the integrity of the blockchain. Beyond monetary incentive, there is desire to participate in the maintenance of a uniquely decentralised network so as to support the Bitcoin blockchain and its underlying principles.

What it takes to mine Bitcoin

One of the core problems Bitcoin solves is the issue of verifying whether one of the owners of a digital coin has attempted to double-spend it. There is a lack of trust in the transaction history of a digital currency, and payees need a way to ensure that the coin they receive hasn’t already been used for another transaction (without needing a third party, such as a bank).

The solution is to eliminate the need for a trusted central authority (like a mint) that checks for double-spending. Instead, transactions must be publicly announced, meaning they are made visible to all participants in the network. This ensures transparency and allows all nodes in the network to be aware of transactions as they occur.

Participants in the network need to agree on a single, chronological history of the order in which transactions were received. In other words, there should be a consensus mechanism that establishes the sequence of transactions.

The payee requires proof that, at the time of each transaction, the majority of nodes in the network agreed that it was the first one received. This proof helps establish the validity and chronological order of transactions.

The Bitcoin blockchain creates a decentralised and trustless system in which transactions are publicly recorded, and the order of transactions is determined by consensus among network participants. This approach removes the need for a central authority and provides a way for payees to trust that the digital coin they receive hasn’t been double-spent. This is why Proof-of-Work and mining are crucial processes to the blockchain technology underlying Bitcoin:

- Transaction Validation: Miners begin the process by collecting and validating Bitcoin transactions from the network’s mempool — a contraction of memory and pool, denoting a cryptocurrency node’s mechanism for storing information on unconfirmed transactions. The mempool acts as a waiting room for transactions that have not yet been included in a block. These transactions represent transfers of Bitcoin from one user to another and include information such as sender and receiver addresses and the amount of Bitcoin being transferred.

- Creating a Block: Miners select a set of valid transactions to include in a new block. This set of transactions is typically chosen based on factors like transaction fees, prioritising transactions that offer higher fees to maximise their potential rewards.

- Hashing: Once the miner has a set of transactions, they bundle these transactions together along with some additional information to create a block. This additional information includes:

Timestamp: The current time when the block is created. This helps maintain the chronological order of blocks in the blockchain.

Nonce (Number Used Once): A random number that miners change in each attempt to solve a cryptographic puzzle. The nonce is a critical element in the mining process as it introduces randomness into the computation.

Cryptographic Puzzle: Miners’ primary task is to find a specific cryptographic hash value for the block they’ve created. This hash must meet certain criteria set by the network, specifically:

● The hash of the entire block (including transactions, timestamp, nonce, and other block data) must be lower than or equal to a target value. This target value is adjusted periodically by the network and is what determines the mining difficulty.

● To find a valid hash, miners repeatedly change the nonce and recompute the hash until they find one that meets the target difficulty. This process involves performing a mathematical operation on the block data (including nonce) and producing a hexadecimal string of a fixed length, which is the hash. - Proof-of-Work: Once a miner finds a valid hash that satisfies the network’s difficulty criteria, they broadcast the new block to the network, along with the nonce and other block information. This valid hash serves as proof that the miner has expended computational work to solve the cryptographic puzzle.

- Block Verification: Other participants in the network, known as nodes, independently verify the validity of the new block. They check that the hash meets the required criteria, that the transactions are valid, and that the nonce was correctly adjusted to find the hash.

- Reward: If the block is accepted by the network, the miner who found the valid hash is rewarded with the block reward (newly created Bitcoins) and the accumulated transaction fees from the included transactions. This reward is added to the miner’s wallet as an incentive for their computational effort.

- Adding to the Blockchain: Once a block is verified and accepted by the majority of nodes in the network, it becomes a permanent part of the Bitcoin blockchain, and the transactions within it are considered confirmed. Miners then move on to mining the next block, repeating the process.

Source: Bitcoin White Paper

Adding a new block to the blockchain is resource-intensive and time-consuming. Consequently, for an attacker to alter a transaction in a previous block, they would need to control the majority of the network’s computational power, known as a 51% attack, which is immensely difficult and costly. As a result, the immutability of the blockchain and the consensus mechanism that underpins it, powered by mining, create a robust security framework that makes it extremely challenging for fraudulent or malicious transactions to be accepted, thus safeguarding the integrity of Bitcoin’s decentralised ledger.

The ‘how’ and ‘why’ of tracking the next halving

When looking to invest, Bitcoin is perhaps the most rewarding asset. With no third party standing to profit from an investor’s gullibility, education, awareness and participation in owning and transacting with Bitcoin is very easy.

Tracking the halving events allows holders of Bitcoin to foresee implications for the Bitcoin ecosystem, including its price, security, and monetary policy. Investors and traders closely monitor Bitcoin halving events because they can have a significant impact on the price of Bitcoin. The anticipation of reduced supply growth often leads to increased demand and price appreciation. Traders use this information to make informed decisions about buying, selling, or holding Bitcoin.

Bitcoin miners are directly affected by halving events, as they see their block rewards reduced by half. Miners need to assess the potential impact on their profitability and make adjustments to their operations, such as upgrading hardware or optimising energy consumption.

Bitcoin users track halving events because they are critical for the network’s security. Halvings ensure that new Bitcoins are issued at a controlled and decreased rate, so as to reduce the risk of inflation and to maintain scarcity.

Bitcoin’s halving events are also integral to its monetary policy. Halvings occur approximately every four years, gradually reducing the rate at which new Bitcoins are created up until a maximum supply of 21 million. This predictable and transparent supply schedule is important to those who value sound monetary principles. And since Bitcoin halvings have historically been associated with significant price rallies, tracking these events allows investors to make better decisions.

Numerous sources are available to monitor Bitcoin halving events and related information. Cryptocurrency news websites provide updates and analysis; blockchain explorer websites allow users to track the Bitcoin blockchain’s progress in real-time, including current block height and information about recent blocks; many exchanges provide news sections and price alerts; and real-time data websites offer countdowns. Pick based on reliability and individual level of understanding.

The future of mining Bitcoin

Halving, as a part of Bitcoin’s monetary policies, has received some criticism on account of “tail emissions”. This term refers to the idea of introducing a small, ongoing, and predictable issuance of new Bitcoins beyond the point when the maximum supply of 21 millions coins is reached. The primary purpose of tail emissions is to address potential concerns that may arise when Bitcoin’s block rewards become too small (and eventually stop altogether after 2140 due to halving events). The concerns include:

- Security and Miner Incentives: As Bitcoin’s block rewards decrease due to halving events, miners may lose their incentives to continue securing the network. If mining rewards dwindle to the point where they are insufficient to cover operational costs, some miners might leave the network. This could potentially lead to centralization and a decrease in network security.

- Sustainability: The security of the Bitcoin network may require a minimum level of rewards for miners to ensure their continued participation and the maintenance of a robust network. Tail emissions could provide a guaranteed income for miners, helping to offset the reduction in block rewards and transaction fees.

- Balance of Supply and Demand: The introduction of tail emissions could help strike a balance between supply and demand in the network. With a predictable issuance of new Bitcoins, miners would have a steady income stream, which might reduce the need for frequent adjustments to transaction fees.

Tail emissions deviate from Bitcoin’s original design principles, such as its fixed supply and predictable issuance schedule. The market, including transaction fees and demand for Bitcoin, is also likely to naturally adapt to maintain network security without the need for additional issuance. Ultimately, Bitcoin’s design principles are aimed at providing a robust and self-regulating system:

- Halving Events: Halving is part of Bitcoin’s monetary policy and is intended to ensure that the total supply of Bitcoin remains capped at 21 million coins. While halving events reduce miner rewards, they are a planned and predictable feature of the network.

- Transaction Fees: Bitcoin’s design allows users to include transaction fees when sending Bitcoin. As the block rewards decrease, the role of transaction fees becomes more significant in compensating miners for their efforts. Users who want their transactions processed quickly are incentivised to offer higher fees, which can make mining economically viable for miners even as block rewards decrease.

- Market Dynamics: Bitcoin’s design is rooted in free-market principles. If the block rewards become too small to cover mining costs, miners may exit the network. However, this reduction in mining activity would lead to a decreased network hashrate, making it easier for the remaining miners to find blocks. This, in turn, would increase the chances of profitability for those who continue mining.

- Immutable Supply: Bitcoin’s design enforces a maximum supply of 21 million coins. This scarcity is a fundamental feature of Bitcoin and is designed to prevent excessive inflation or devaluation of the currency over time. Lost Bitcoins (of forgotten passwords, lost private keys, etc.) also contribute to the overall scarcity of Bitcoin.

- Consensus Mechanisms: The reliance on a decentralised consensus mechanism (Proof-of-Work) where miners compete to add new blocks to the blockchain ensures security and integrity of the network. While miner incentives are essential, Bitcoin’s design also prioritises decentralisation and security.

- Community and Development: Bitcoin has a strong and active community of developers, miners, and users who engage in open discussions and debates about the network’s future. Any proposed changes, including the introduction of tail emissions or other modifications, would require consensus within the community.

Bitcoin’s monetary policy is designed to have a fixed supply of 21 million coins, and this supply will be reached through a series of halving events that reduce the block rewards over time. Once the 21 millionth Bitcoin is mined, there will be no more new Bitcoins created, and miners will rely solely on transaction fees for their income. Changing any of Bitcoin’s original principles disturbs its utility much more significantly than any changes may benefit miners.

Bitcoin’s scarcity, decentralisation, and security is what makes it a good store of value. Fixed supply makes Bitcoin resistant to inflationary pressures. Its decentralised nature, operating on a global network of nodes and miners, ensures that it is not controlled by any single entity, government, or central authority, reducing the risk of manipulation or devaluation. Bitcoin’s robust security model, based on cryptographic principles and a resilient Proof-of-Work consensus mechanism, protects it against fraud and unauthorised changes to the blockchain. Together, these attributes make Bitcoin paramount for everyone seeking a reliable and censorship-resistant store of value in an increasingly digital and uncertain financial landscape.